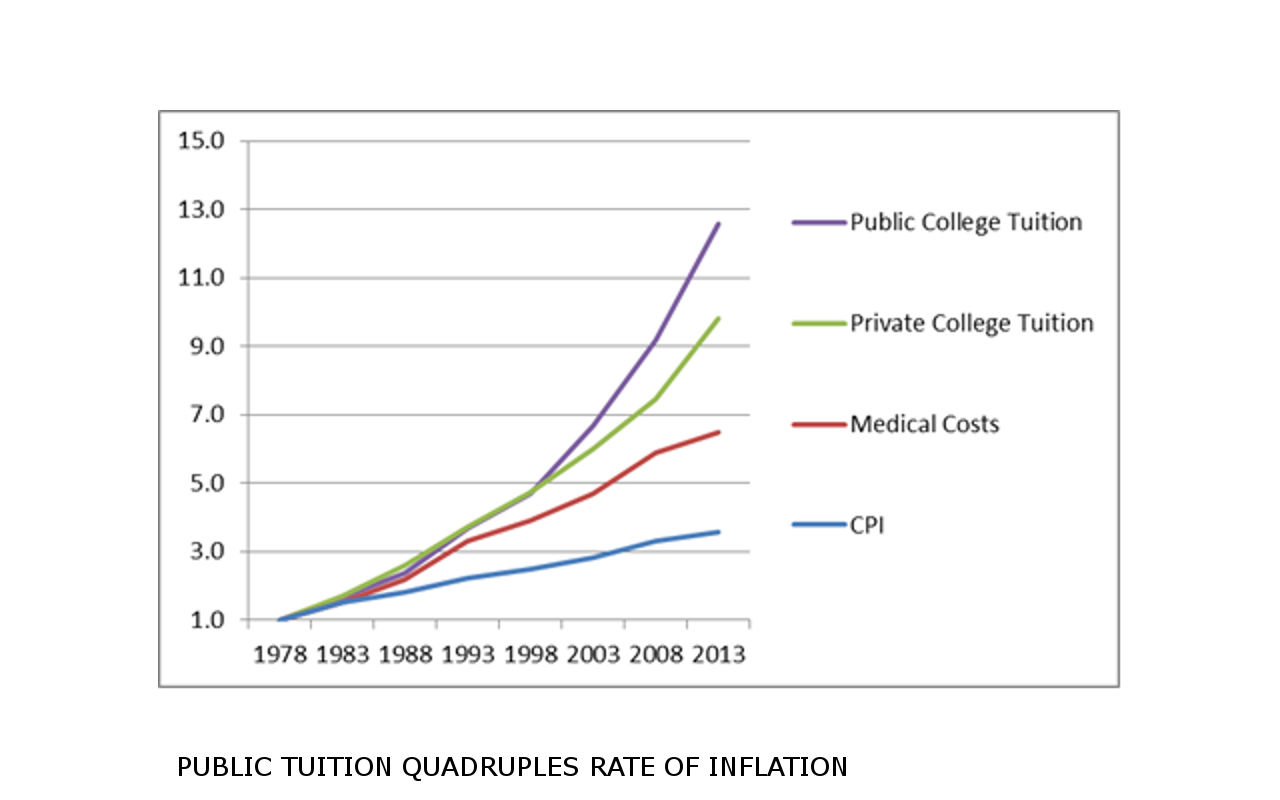

Rising medical costs have long been in the public eye, and for good reason. Over the last thirty-five years, medical costs have grown at a rate double that of inflation. With wage-earner income remaining essentially constant, the burden on the average person shot up six-fold.

At the same time, public college tuition skyrocketed over twelve times, nearly doubling the rate of medical increases. Like heart disease, the “higher education silent killer” has already taken its toll—$1.3 trillion in student-loan debt that has limited access for millions of people and greatly curtailed their economic purchasing-power.

The chart below graphically exemplifies this travesty:

Tracing the Consumer Price Index from 1978 illustrates the three-fold inflationary surge. As the most prosperous nation in the world we’ve adjusted to these costs. Had other national indices paralleled these increases we would have avoided the recent recession and would not have had to pay for the stimulus package.

Private university tuition during this period escalated ten times, more than tripling inflation. Yes, that’s right, the percentage increase for public university tuition ballooned at a higher rate than that of private universities!

Trying to address these costs, the federal government increased Pell Grant funding by a whopping 1700%. But, because of the spiraling costs of higher education and the soaring number of students, the amount of the tab covered by these grants dropped from 72% to 34%.

Horrific as these percentages may be, the dollar impact on individual students was even more exorbitant. In 1997 Pell Grants paid for 72% of the costs for students attending a public university. The remaining $688 was paid for by students. By 2013, the federal contribution had dropped to 34%. (Had university tuition costs followed inflationary rates, students would have paid three times the $688 or a total $2064.) Instead, due to skyrocketing tuition, the average student at a public university paid $8655. Geez!

| 1997 University Tuition | 2013 University Tuition | |||

| Federal Contribution | Students Paid | Federal Contribution | Students Paid | |

| Public | 72% | $688 | 34% | $8,655 |

| Private | 35% | $2,958 | 15% | $29,056 |

During this timeframe universities did nothing to change. They plodded along like the proverbial dinosaur acting as if nothing had changed. Corporations faltered and failed. Kodak almost died. General Motors was too big to collapse but it did.

There are countless ways in which higher education could reign-in spending, starting first with how personnel are evaluated—assessing staff by the value they add, measuring faculty by the qualitative learning they produce, and evaluating leaders by their budgetary effectiveness.

Inside the academy presidents could take simple cost-cutting actions to reduce the bloated size of mid-management. They could apply the same concepts to reduce inefficiencies in the way faculty loads are determined. Add-on curriculums could be streamlined; thereby, eliminating deadwood-courses taught by “retired-on-the-job” professors.

Similar changes must be made in big-time athletics. The most recent five-year study found only eight universities of the nation’s one hundred and twenty-five largest programs made a profit. The rest of the institutions drained millions of dollars from their university coffers.

Governors and state legislators need to tie new funding to cost-cutting measures. Board members need to demonstrate greater fiscal responsibility. Budgetary expertise should be added to the selection criterion for presidents and annual financial training made a condition of employment.

The federal government, too, has failed miserably in its role to serve and protect the best interest of the general public. There are no checks and balances for higher education. University tuition increases are simply passed onto students, mushrooming student-debt levels even more.

Some members in Congress have called for “forgiveness programs” in an effort to reduce the loan burden on student, but no one has proposed “common sense” changes that build upon our core values. Such thoughts are not outlandish. For example:

• Ballooning loan default rates could be greatly curtailed by turning the process over to the IRS.

• Rather than following a principle of one-size fits all, Pell Grant awards could be adjusted higher for fully-qualified students. (Today, over half of the students entering college are underprepared, needing to take at least one remedial course in reading, mathematics or writing.)

• Pell Grants awards could be pegged to inflation so when an institution raises its tuition above the norm, awards to students would go down. (When students start walking it won’t take long for universities to get the message.)

• Significantly more emphasis could be placed on the use of college work-study opportunities: thereby, lessening the amount of loans and encouraging students to earn more as they go.

• Incentives could be built into Pell Grants that encourage students to graduate sooner, focusing subsidizes on graduation requirements rather than elective courses taken for the fun of it.

Clearly, higher education must face its fiduciary responsibility, but without external motivation from Washington, little change will be forthcoming from our great universities. It’ll be more of the same—business as usual—escalating costs, less opportunity for students and more debt.

We can’t afford to risk the demise of one of our country’s greatest resources. Action must be taken to reform higher education; once again, making high quality education available to all who qualify. Pass this information on to friends and colleagues – – and let’s huddle together to develop a plan for bringing the financial management of higher education institutions back under control.

Les Cochran, Former President

Youngstown State University